Choosing the Best Amount of Packaging for Your Product

Products need enough packaging to prevent damage, but no one wants to spend more on packaging than needed. Packaging and pallet decision-makers alike will benefit from having a better understanding of downstream supply chain costs.

Over the last several years, consumer products supply chains have trended towards more frequent deliveries and smaller order sizes. Such an approach has enabled retailers to minimize their pipeline inventory while promoting better product availability – having the products that customers are looking for, on the shelf. However, such a strategy poses different challenges.

Smaller orders may require product suppliers to build multiple SKU pallets for inbound delivery to retail distribution centers. Such an approach translates into extra handling during the assembly of the order, as well as at the distribution center when those same orders are sorted and received. Furthermore, smaller, more frequent retail store orders may result in more case touches for distribution center personnel as they are challenged to stack stable pallets for retail store delivery.

According to experts, around 90% of product damage in the CPG supply chain occurs at the DC or retail location. Further downstream in the supply chain there are more interactions between people and products, which increases the likelihood of damage.

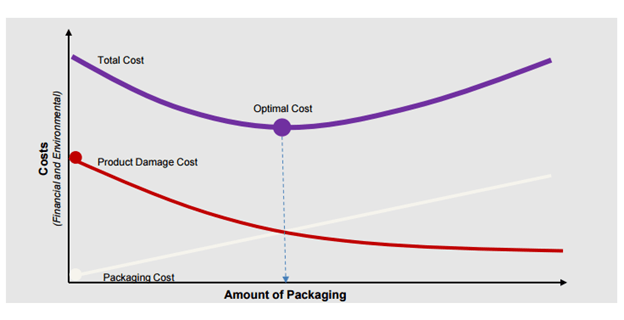

So what exactly is the best amount of packaging for your product? Ultimately, it is the amount that delivers the lowest total packaging cost. Take the graph below.

The connection between packaging cost and the amount of packaging is shown in white, while the interaction between the cost of product damage and the amount of packaging is revealed in red. The total packaging cost per package (the sum of packaging cost and damage cost, is outlined in purple.

The lowest cost per package is located at the intersection point of cost and damage. At this point, an extra penny spent on a package would generate a saving of under a penny’s worth of product damage reduction. In the other direction, cutting the amount of packaging by a penny would result in more than a penny’s worth of incremental damage.

While this approach seems obvious, we are left to ponder why product damage is still an ongoing issue. One reason might be a lack of visibility into supply chain damage that happens further downstream.

If the package design does not reflect all product damage costs associated with a package, then the packaging decision will be suboptimal. A suboptimal package design leaves an unrealized opportunity for supply chain improvement.

By better accounting for actual costs, the product damage cost shifts upward, resulting in a new intersection point – one that dictates an additional investment in a package, as shown in Figure 2, below.

Another way to visualize packaging optimization is with the Innventia AB Model (formerly known as the Soras Curve), shown below.

When a product is underpackaged, excessive damage results in a negative environmental impact. When a product is overpackaged, likewise there is a negative environmental impact resulting from excessive resource consumption and residuals.

When it comes to determining whether or not your package provides the perfect amount of product protection, a collaborative supply chain process is essential. With packaging as with pallets, more accurate supply chain feedback can make a positive difference.

Armed with better information designers and decision-makers can better identify costs downstream, enabling them to select the best package – or pallet – for the job.